Will qMRI take over the world?

If it is so powerful, why clinical imaging is still – almost purely – conventional?

1If qMRI is possible and powerful, why is clinical imaging still conventional?¶

“The court found that Fonar failed to establish the existence of standard T1 and T2 values, which are limitations of the asserted claims...” (GE vs Fonar 1996, U.S. Fed. Cir.)

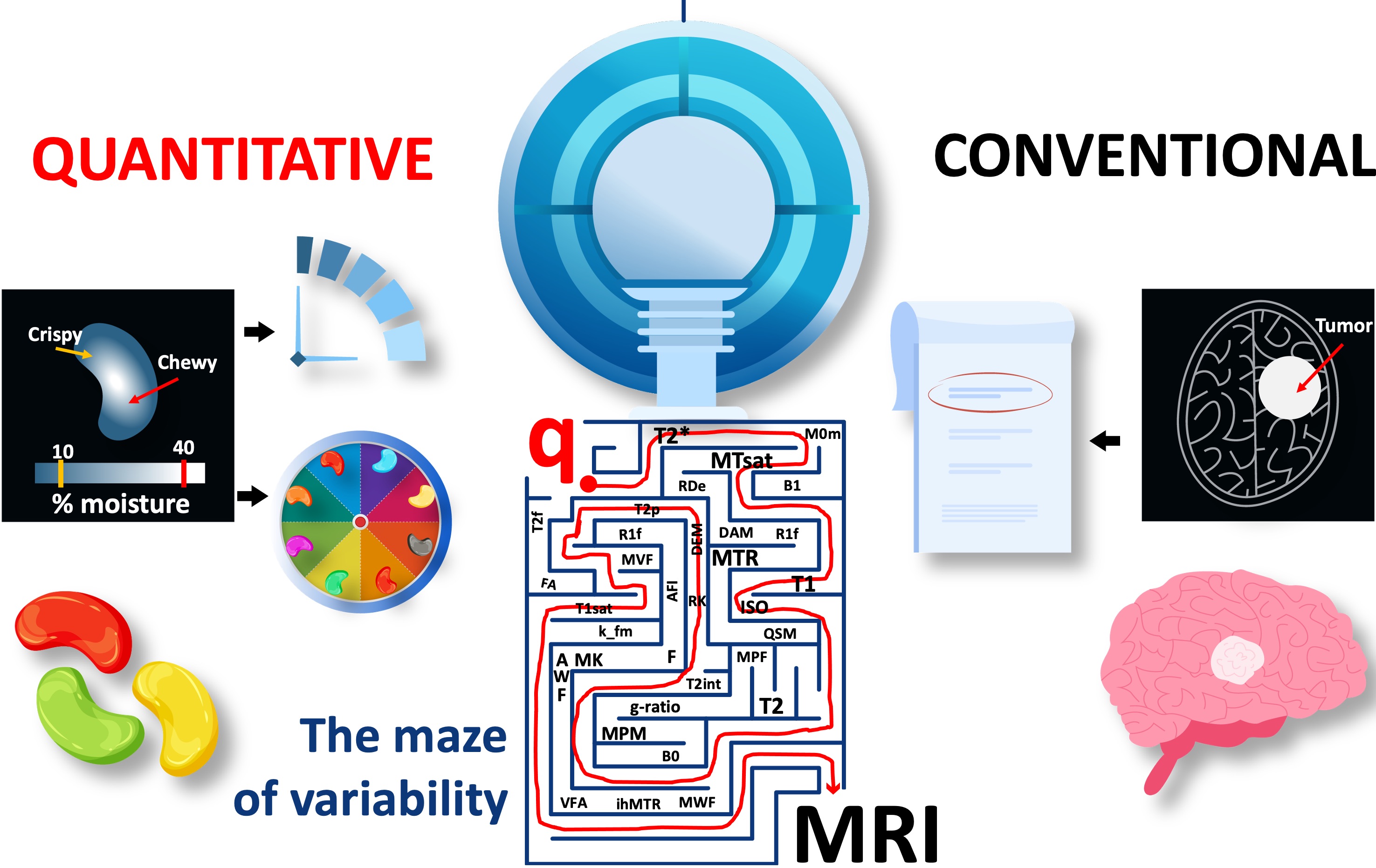

This is partly because of the inherently complex make-up of the human body, where sensitivity alone is not enough to tease out biological variability. Quantifications should also be specific to the targeted microstructure, such as the myelin in the living human brain. For this purpose alone, the literature offers more than 30 methods for quantifying myelin at varying methodological complexity, yet they all appear to be statistically indistinguishable in specifying myelin (Mancini et al., 2020). This indicates that a lack of methodological extensity is not the culprit preventing qMRI from clinical use. Quite the contrary, there is an abundance of solutions, yet we cannot make an informed decision about which method to use. This problem has multiple roots and Figure 2.23 outlines the components of a qMRI study for identifying them.

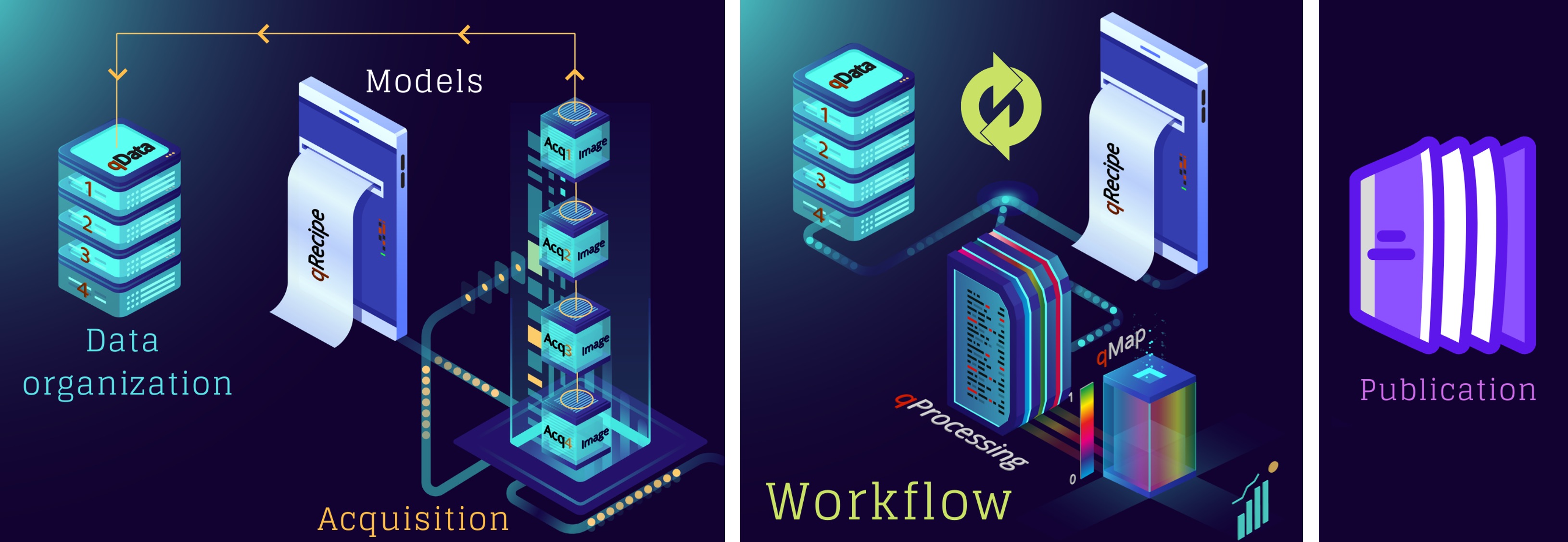

Figure 1:An illustration of the components that make up a qMRI study.

1.1Vendor-native differences challenge the reliability of qMRI¶

Every qMRI study starts with the acquisition of a set of conventional images. This is often achieved by altering protocol parameters according to the signal representation of the respective pulse sequence, i.e. successive runs. As previously shown in the SPGR example for T1 mapping (Figure 2.20), there are various parameters that are vital to the measurement accuracy and precision. In general, strict metrological standards are established for the manufacturing process of any medical device expected to fulfill some accuracy requirements. For example, all the ventilator vendors are obliged to disclose their measurement uncertainty for inspiratory oxygen concentration (ISO 80601-2-12:2011). However, MRI is exempt from such a class of essential performance assessments on the accuracy and precision, given that the medical diagnoses using conventional MRI depend on qualitative feature recognition (Figure 2.1). In turn, design considerations that matter to the reliability of qMRI measurements fall through the cracks of the device manufacturing and programming processes. Although this is understandable from a vendor’s cost-effectiveness standpoint, it bears dire consequences on the quantitative applications.

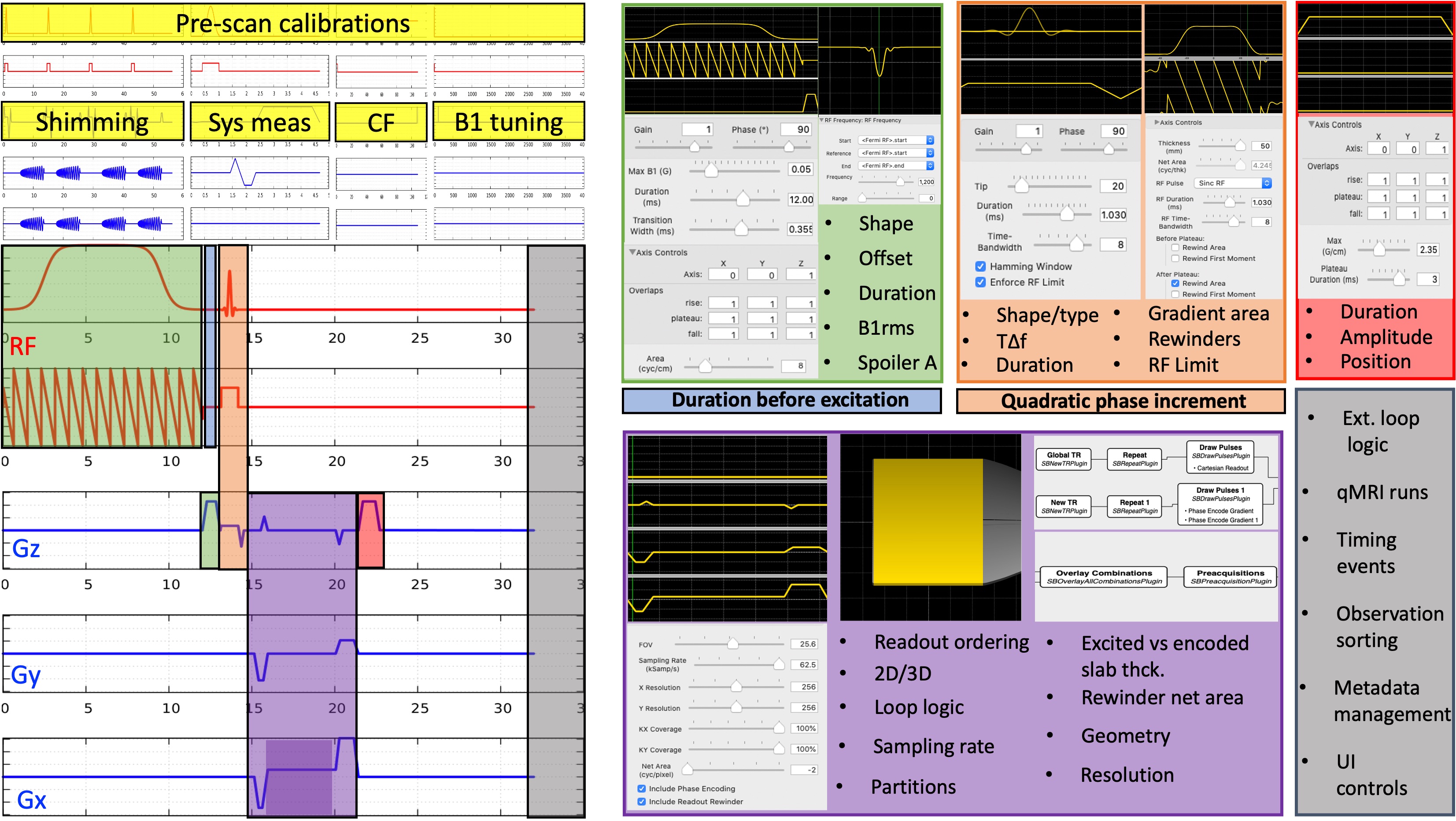

Figure 2:Choices involved in the implementation of a magnetization-transfer weighted spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) sequence are shown for all the gradient and RF waveforms involved.

Even for the simplest sequence implementations, there may be several parameters that matter to quantification, but are hidden from the end user. Figure 2.24 shows the implementation- level parameters that are available after the type/shape selections were made for an SPGR sequence with a magnetization-transfer saturation pulse. In addition to the sequence itself, pre-scan calibrations such as shimming, center frequency tuning and transmit gain adjustments are other factors that affect the measurement accuracy. For example, neither of the major vendor implementations enable the selection of spoiling gradient area (Figure 2.20a), RF spoiling regime (Figure 2.20b,c), magnetization transfer (MT) pulse specifications, ex- citation pulse type or the ordering of the observations (Figure 2.24). The more advanced the sequence, the more implementation choices come to the surface. These restrictions and unknowns brought by vendor-specific sequence implementations trap tens of qMRI measurements into a maze of variability and prevent them from reaching the clinics (Figure 2.25).

After the raw data is acquired, it has to be reconstructed to generate images, which is yet another process with a wide range of options to choose from. Therefore, properly formatting and making the raw data accessible is a non-trivial interim step for the provenance of the following steps. In addition, the relationship between the reconstructed images and the grouping logic entailed by the qMRI model should be retained along with sufficient metadata. Even though there is an emerging data standard for organizing the raw data (Inati et al., 2017), there is not a community consensus on how to organize qMRI datasets (Figure 2.23). This creates idiosyncrasies, challenging interoperability and decreasing efficiency of processing qMRI data.

Figure 3:The current landscape of quantitative MRI is a maze of variability for amazing methods. A complete recipe is needed to chart out the path towards clinics.

There are dozens of publications introducing new qMRI methods, yet a majority of these implementations are kept within their labs of origin, making it challenging to reproduce qMRI studies. This is partly caused by the vendor restrictions. Nonetheless, it is generally possible to share the workflow components of the developed methods. Figure 2.23 shows that all

qMRI methods share a common methodology at their core: a signal representation (qRecipe) that relates a set of parametrically linked MR images (qData) to some microstructural and physical features (qMap) by computation (qProcessing). Although these ingrained attributes exist at a conceptual level in the source code developed by independent developers, there is not a consensus on how to represent them in a programming paradigm. Even though 80% of the source code made available by the MRI developers share the same programming language (MATLAB) (Boudreau, 2019), there is still a need for a common framework for the development of qMRI methods in MATLAB to make implementations easier.

To summarize the problems mentioned above, there are three outstanding issues that hinder the standardization of qMRI:

- Most methods are developed using in-house code that is difficult to distribute, chal- lenging the accessibility and reproducibility of qMRI studies.

- The lack of a qMRI data standard poses an interoperability challenge for open-source solutions aiming at making qMRI methods publicly accessible.

- The unknowns involved in the implementation of commercial pulse sequences constitute a substantial source of (vendor-specific) variability in fitting quantitative parameters using voxel brightness data.