Origins of MRI - A Visual History

From quantum to macro-scales

1A pictorial and historic journey into how MRI works¶

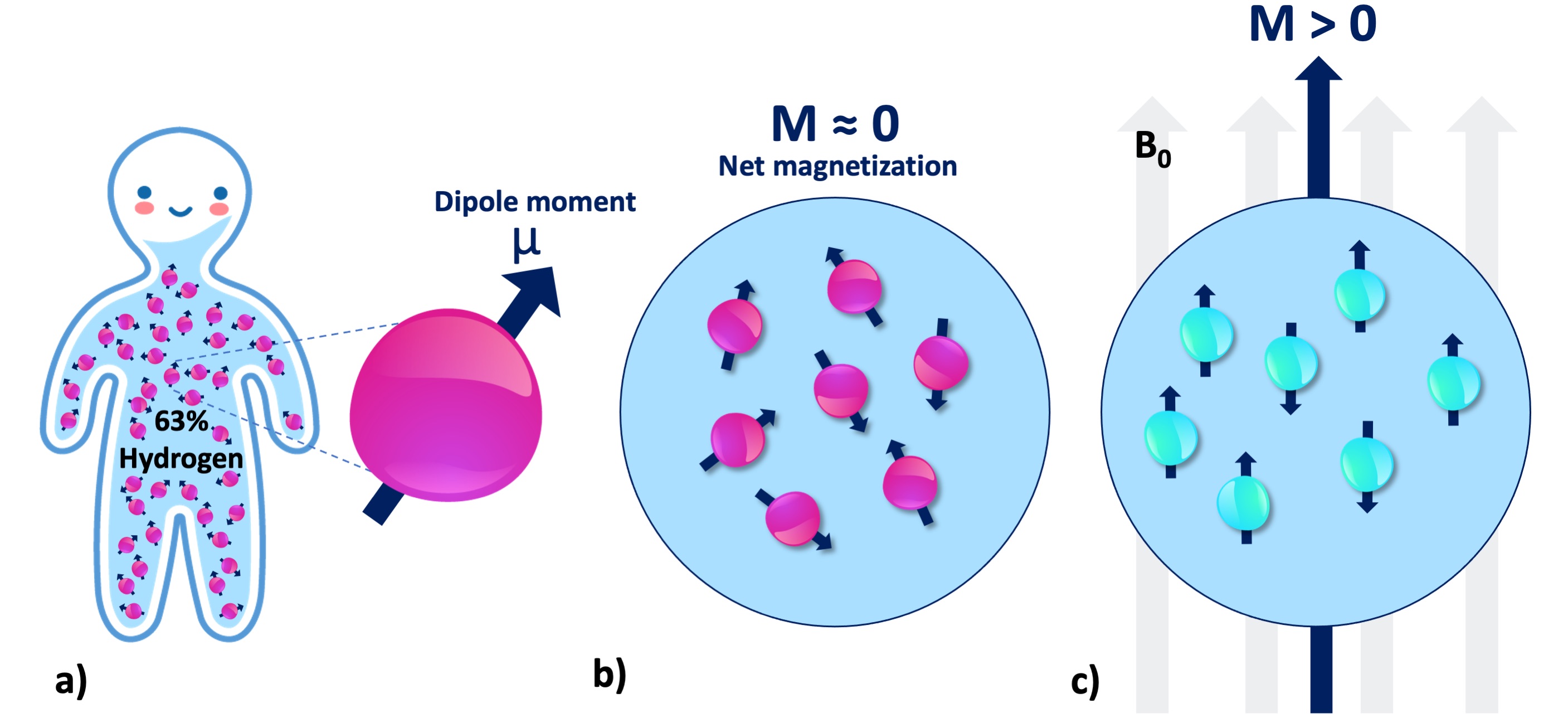

The human body can be seen as a complex compartmentalization of water, fat, protein and minerals at every level of its organization from atoms to organs (Siri, 1956). At the atomic scale, nearly 63% of the atoms in the human body are hydrogen atoms (Osmera and Vanicek, 1940), which consists of only one proton and one electron. It is this simplicity that makes hydrogen the most studied atomic structure in quantum mechanics, which eventually lead to the development of MRI.

Once the mass and charge of the hydrogen particles were known, nobody suspected that there was another hydrogen property to be discovered. The study of hydrogen was revolutionized when two scientists in their mid 20s, Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit, wrote together the first article about the nuclear spin in 1925 (Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit, 1925). They were afraid to submit their work, because the celebrity physicist Lorentz deemed their idea “unphysical”. At that time, Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit were working under the supervision of Zeeman and Ehrenfest, yet Zeeman and Ehrenfest omitted their names from the article, deciding to use the youth of their protegees as a shield against any backlash (Halpern, 2017). What was feared to be a foolish mistake was then accepted as a built-in feature of any fundamental particle in the universe, just like the mass and charge. This quantum property – spin – is the key to understanding how MRI works.

1.1Getting on the same wavelength with a single hydrogen in the quantum realm¶

28 years before his student would give an underlying explanation, Zeeman showed that the energy levels in an atom change under the influence of a magnetic field, an effect known as Zeeman’s splitting (Zeeman, 1897). This is particularly important for hydrogen, because unlike a magnetic field, an electric field does not lead to an energy difference between its spin configurations (i.e., does not split) (Feynman et al., 2015). Hydrogen is assumed to have four (ground) spin states, created by the combinations of two up and two down spins from its proton and electron. Each combination constitutes a different energy level. The difference between these energy levels is so small that their separation is defined by the term “hyperfine splitting”. What encourages the hydrogen to exhibit more than one energy level is the presence of a uniform magnetic field (B0). This effect opens a communication line to interact with hydrogen, yet it takes some special effort to start a conversation.

1.1.1Picking up a hydrogen atom in the quantum realm: The perfect match¶

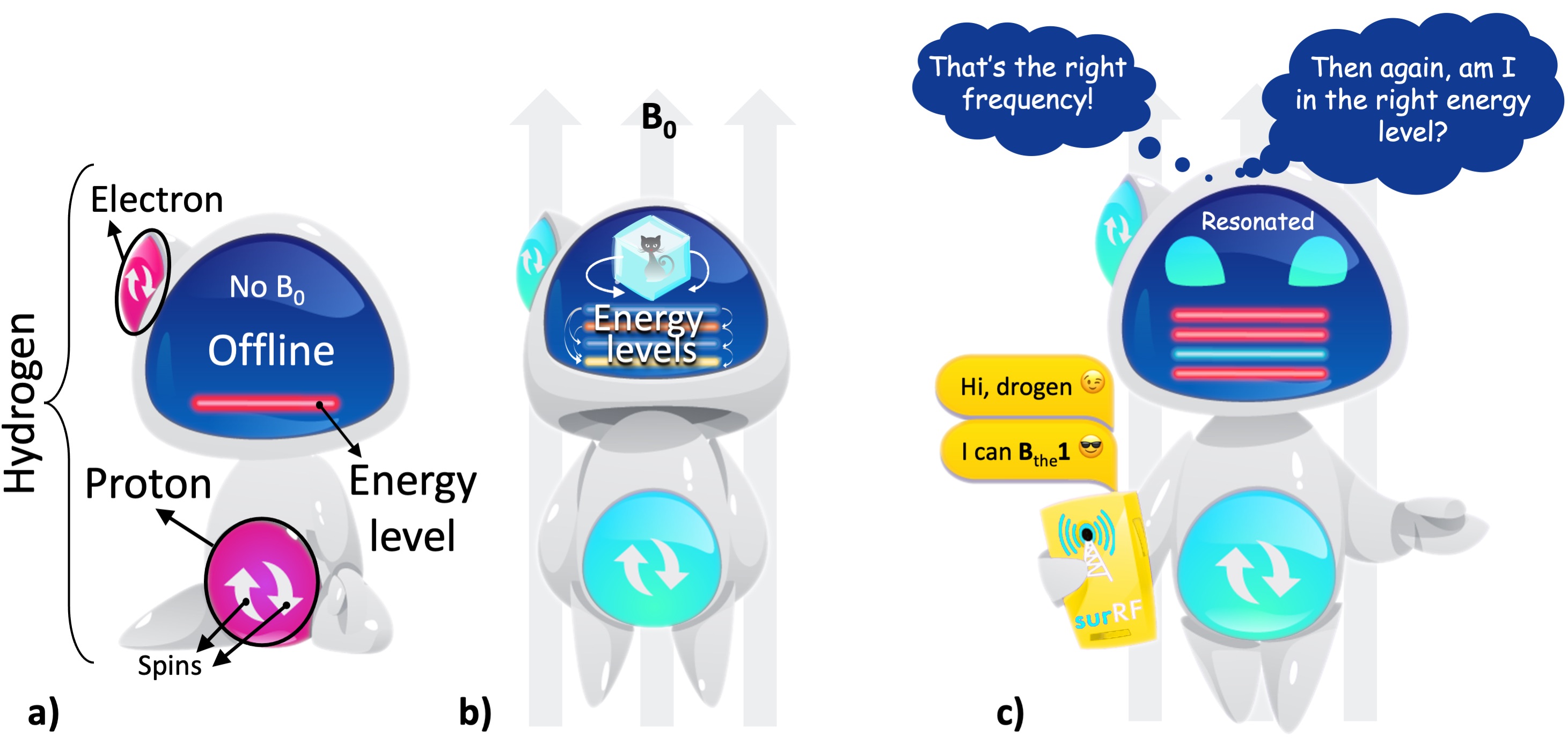

The hydrogen atom comes online only when standing up under the influence of a magnetic field (Fig. 1a,b). The chances of getting a response from the hydrogen firstly depends on whether our message kindles just the right amount of excitement for it to switch between those hyper-finely separated energy levels (Fig. 1). Although it almost seems like the hydrogen is sidestepping a conversation, all it takes is finding the right wavelength to meet this first requirement. Six years after the introduction of the spin concept, Rabi and Breit finally discovered that to resonate with hydrogen’s energy levels, we need to send our messages in the radiofrequency (RF) range of the electromagnetic spectrum (Breit and Rabi, 1931).

However, not all hydrogen atoms behave the same. We need to be familiar with the peculiarities of the hydrogen we are in touch with. There are two key attributes: where is the hydrogen from, and in which energy state it is when our resonating message is delivered (Fig. 1c). The last nuance to get on the same wavelength is finding the right angle to approach it. If we meet all the requirements, we will see the hydrogen getting excited and responding to us within a certain RF bandwidth.

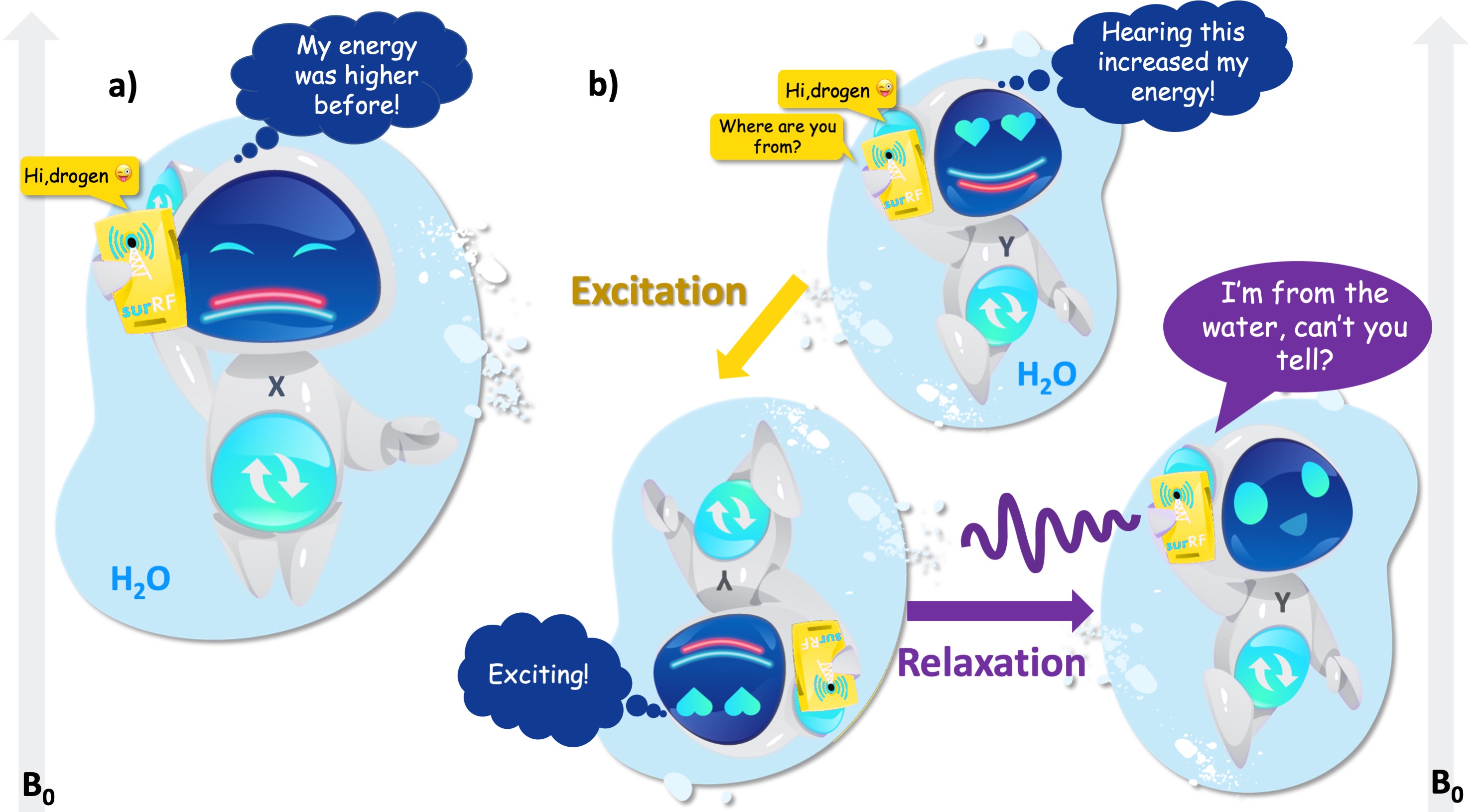

For the imaging of the human body using MRI, we will be mostly communicating with the hydrogen from the water (Fig. 2). In general, water hydrogens are more easy-going because their electron spin states are balanced, so we are only concerned with the energy levels emerging from their nuclei. This is why we call this pick-up line the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Figure 1:a) A hydrogen atom has one proton and one electron, with each particle is assumed to have two possible spin states for simplicity (up or down). In the absence of a magnetic field, the atom is at a random orientation (offline) and shows a single energy level (the red line). b) Under a uniform magnetic field (B0), the atom is aligned with the field (online) and shows multiple energy levels (the colored lines). These energy levels are in quantum superposition: all the levels simultaneously exist and we can only determine one state upon observation. This behaviour of the energy levels is represented by the Schrödinger’s cat2. c) Once it is online, the hydrogen atom can be contacted through a communication line that operates within the radiofrequency (RF) range.

Fig. 2 shows that the hydrogen from water has two energy levels under a uniform magnetic field: low energy and high energy. If the resonating message flips the hydrogen’s energy state from higher (red) to lower (cyan) state, the result is a “radio silence” (Fig. 2a), i.e. the hydrogen gives up a small amount of excess energy instead of a response. But if the resonating message elevates the hydrogen’s mood from lower (red) to the higher (cyan) state, the hydrogen gets excited (Fig. 2b). After the message is delivered, we will finally get a response as the excitement quickly fades away. This final process is termed “relaxation”, which is of essence to the MRI contrast, because the message carries information about where that hydrogen is from.

Figure 2:a) After receiving the call, the hydrogen atom from water switches from the higher (red) to the lower (cyan) energy level and refuses to answer. b) When the RF input switches its energy from the lower (red) to the higher level (cyan), the atom gets excited. While returning to its initial state, the atom responds.

The tone in the response shifts slightly if the hydrogen is from non-water molecules, e.g., fat or protein. This slight difference is caused by the amount of negative energy a hydrogen is surrounded by, which interferes with the contribution of hydrogen’s electron to its energy state, namely shielding. The more negative energy around the hydrogen, the shorter the response. It appears that the positive effects of being near water on the energy levels tran- scends scales, from humans themselves (Cracknell et al., 2016) to the hydrogen atoms that make up them (Lawrence and McDonald, 1966).

So far we looked at the quantum-level interactions between the hydrogen atom and RF energy, and tied it with the NMR phenomenon. However, in reality, we don’t have access to observed NMR effects at such a fine-grained level; because no appropriate instrumentation exists, and quantum-jitters make such instrumentation nearly impossible (Erkintalo, 2021). For example, we cannot detect the uncertainty of a single hydrogen atom’s energy levels. The best we can do is to visualize the concept using metaphorical illustrations, such as using Schrödinger’s cat to imply the quantum state of the hydrogen’s energy levels in Fig. 1b. Until we observe the consequences (whether the hydrogen will respond to our resonant message or not), all the energy levels are assumed to be in quantum superposition, even for only two energy states of proton spins as shown in Fig. 2. To achieve observational accuracy, we need to move from the uncertainties of the energy levels to a probability of getting a response to our resonant message, which is what we will look at in the following section.

1.1.2Finding the perfect quantum match is not practical, but there are plenty of fish in the sea¶

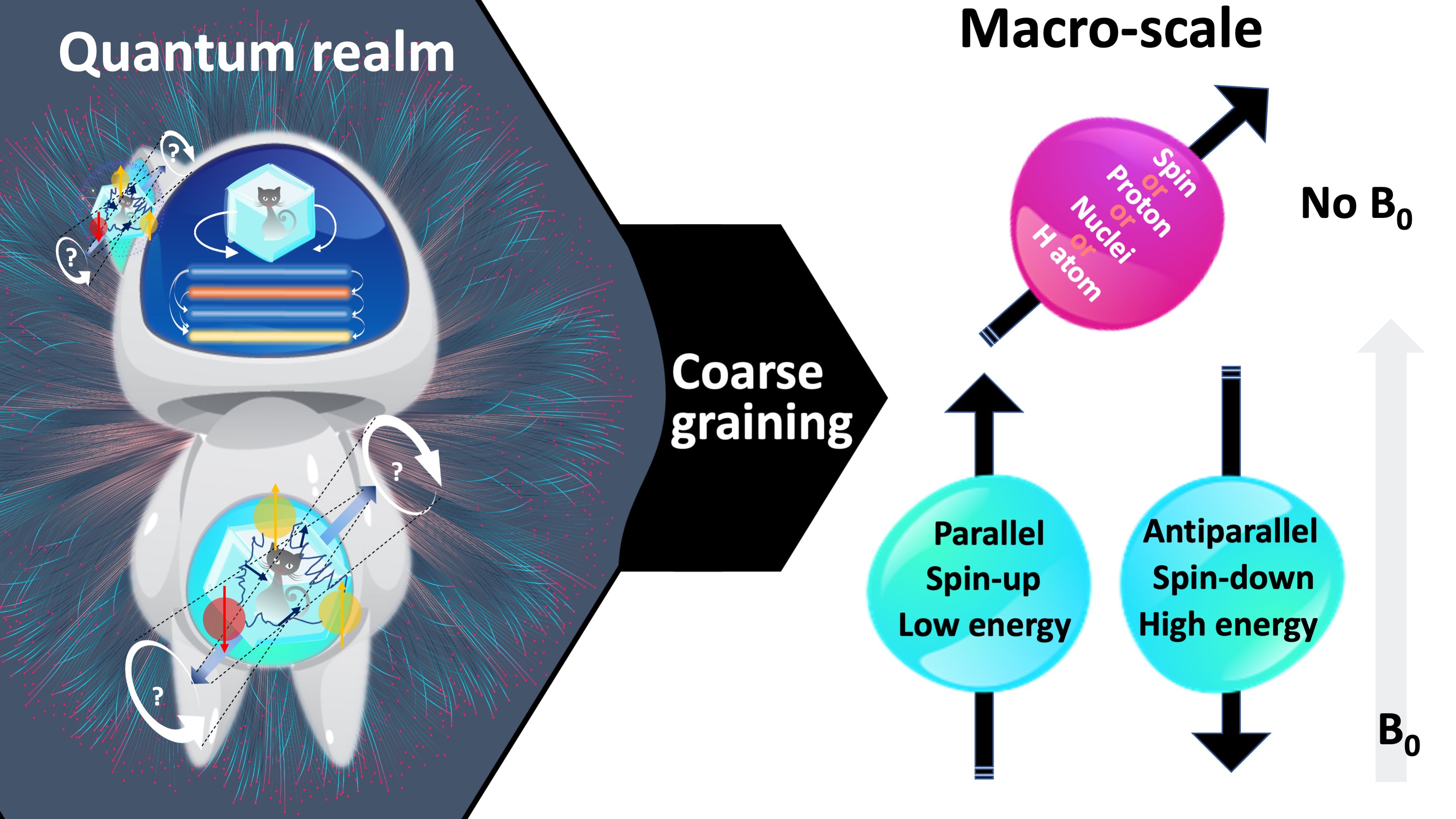

We can harness the benefits of NMR without having a complete theoretical understanding of the underlying quantum interactions (see proton spin crisis (Siegel, 2017)), because these effects simply smooth over at the macroscale. At this point we will leave the online dating analogy behind, because even at the smallest macroscopic scale, “there are plenty of fish in the sea” (Fig. 2a). At the level where an NMR measurement is technically feasible, we will be concerned with a large pool of hydrogen atoms. Here, the individual behaviour of particles becomes useless for characterizing the system in aggregate. This concept of integrating over microscopic details to achieve a compact and useful system description is coarse-graining (Fig. 3).

Figure 3:At the macro-scale, the quantum mechanical behaviour of individual hydrogen atoms is averaged over, i.e., coarse-grained. Fig. 2 illustrates a fine-grained description of the behaviour of a single hydrogen atom in absence and presence of a magnetic field. After coarse graining, the representation simplifies to an arrow passing through the center of the proton, which is aligned parallel (i.e., spin-up, low energy) or antiparallel (i.e., spin-down, high energy) with the magnetic field (blue), or at random if the field is absent (pink). Follow- ing coarse-graining, the terms spin, proton, nuclei or hydrogen can be used interchangeably.

Fig. 3 shows how the representation of a hydrogen atom is changed after coarse-graining microscopic details of spin interactions. From this point onward in this document, hydrogen will be illustrated as shown in Fig. 3, and used interchangeably with the terms spin, proton and nuclei. To refer to the energy level associated with a single hydrogen atom, we will describe the magnetic moment (Fig. 4a): If the proton was merely a rigid body, its rotation about an imaginary axis that passes through its center would create a small angular momentum aligned with that axis. Given that the proton is a charged particle, it also creates a microscopic magnetic moment (μ) as a result of this rotation, which is a vector in the same direction (Fig. 4a). The ratio between the angular momentum and the magnetic moment yields the gyromagnetic ratio (γ), which is 42.59 MHz for the hydrogen at 1 Tesla (T) magnetic field. This frequency at which the spins rotate is commensurate with the magnetic field strength. The product of the gyromagnetic ratio and the field strength (γB0) yields the Larmor frequency, at which the RF energy must be delivered to achieve nuclear resonance.

Figure 4:a) There are millions of protons (i.e., spin or nuclei) even at the smallest macro- scopic unit volume relevant to the MR imaging of the human body. Each individual proton exhibits an infinitesimally small magnetic moment (μ). b) Without B0, the protons in a spin pool exhibit random alignment. c) In presence of B0, the spins are aligned with the magnetic field (parallel or antiparallel), giving rise to a net magnetization (M).

At the macroscale, we will be concerned with millions of protons at once (Fig. 4a), even for a unit volume of 1mm3. Absent an external magnetic field, magnetic moment vectors are oriented at random (Fig. 4b). When a magnetic field is applied, they are aligned either parallel (spin-up, low energy) or antiparallel (spin-down, high energy) with the applied field (Fig. 4c). Given the vast abundance of these spins, the relevant question becomes: which spin configuration is dominant? According to the second law of thermodynamics, if the spin system is at thermal equilibrium, i.e., no energy enters or leaves the system, the entropy of that spin system increases (Carnot et al., 1899). This omnipresent tendency toward disorder favors low energy (Ferris, 2019). Therefore, the spin system tends to have slightly more low-energy hydrogen atoms (spin-up, parallel). Although the difference is as small as 40 per million protons (Webb, 2016), a net magnetic magnetization (Fig. 4c) can be observed by a real-world NMR experiment.

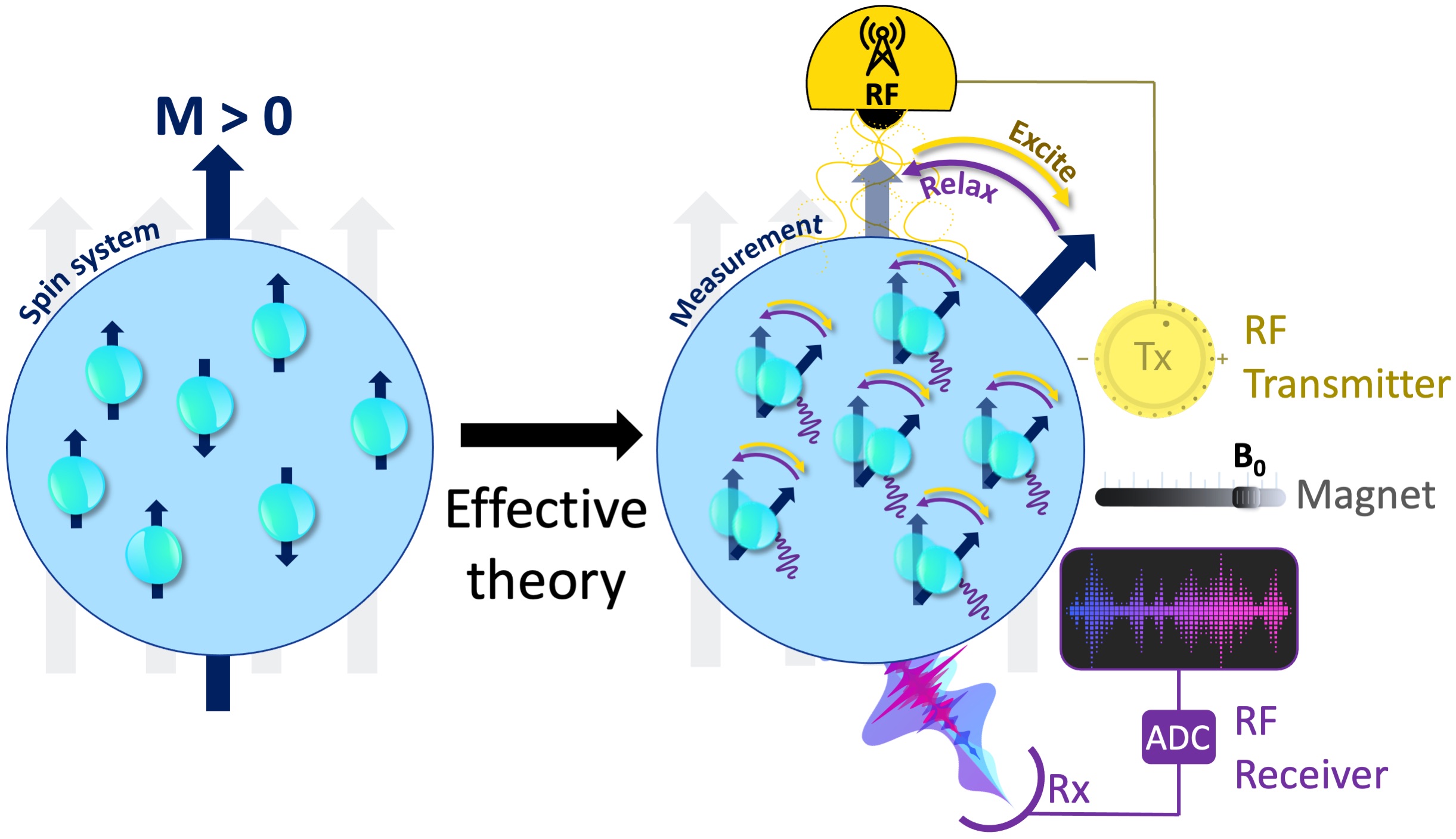

Figure 5:The measurement instrumentation is concerned with the relevant degrees of free- dom and an effective theory that explains how these coarse-grained variables respond to the perturbations of the measurement system. Some fundamental components of an MRI mea- surement include a uniform magnetic field generator (i.e., a magnet), an RF transmitter (Tx, yellow), an RF receiver (Rx, purple) and an analog-to-digital converter (ADC).

To perform a real-world measurement, an effective theory is needed to describe how the coarse-grained features of the targeted system (Fig. 4) changes upon interaction with the measurement instrumentation (Fig. 5). The effective theory of relaxation for the bulk magnetization M was described by Felix Bloch in 1957, laying one of the cornerstones to bring MRI to reality (Bloch, 1957). A basic instrumentation to study the relaxation of a spin system is depicted in Fig. 4c, including a uniform magnetic field (B0) generator, an RF transmission system tuned to the Larmor frequency and an RF receiver coil followed by an analog-to-digital converter (ADC). The following section describes how Bloch equations explain the macroscopic behaviour of the net magnetization and how MRI scanners make use of this effective theory to create images.