The Double Helix and MRI Part 2: qMRI-BIDS

Previously

In part 1, we compared DNA sequencing to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to illustrate that although both fields utilize many of the same statistical techniques, they examine fundamentally distinct types of information. Genetic data contains quantitative information, such as the sequence of base pairs obtained through DNA sequencing, while conventional MRI data contains qualitative information, such as unitless intensity values obtained through MRI scans. To address this distinction, researchers have developed quantitative MRI (qMRI), which allows scientists to work with quantitative data output as 3D images with units. In the following section, we will continue to draw parallels between genetics and MRI, albeit on a more metaphorical level.

But what about data standards?

MRI depends on the sampling of a signal that originates from protons that exist on a scale of around 10-12 mm (Antognini et al., 2013)), yet each voxel is on the order of 1 mm. qMRI data acquisition and processing therefore demands high methodological rigor. However, before thinking of ways to leverage this technique and resolve many debilitating diseases and perennial philosophical questions (once and for all!), you need to lay out the less glamorous details: how do you name and organize your data files in order to minimize errors, facilitate data sharing and optimize reproducibility?

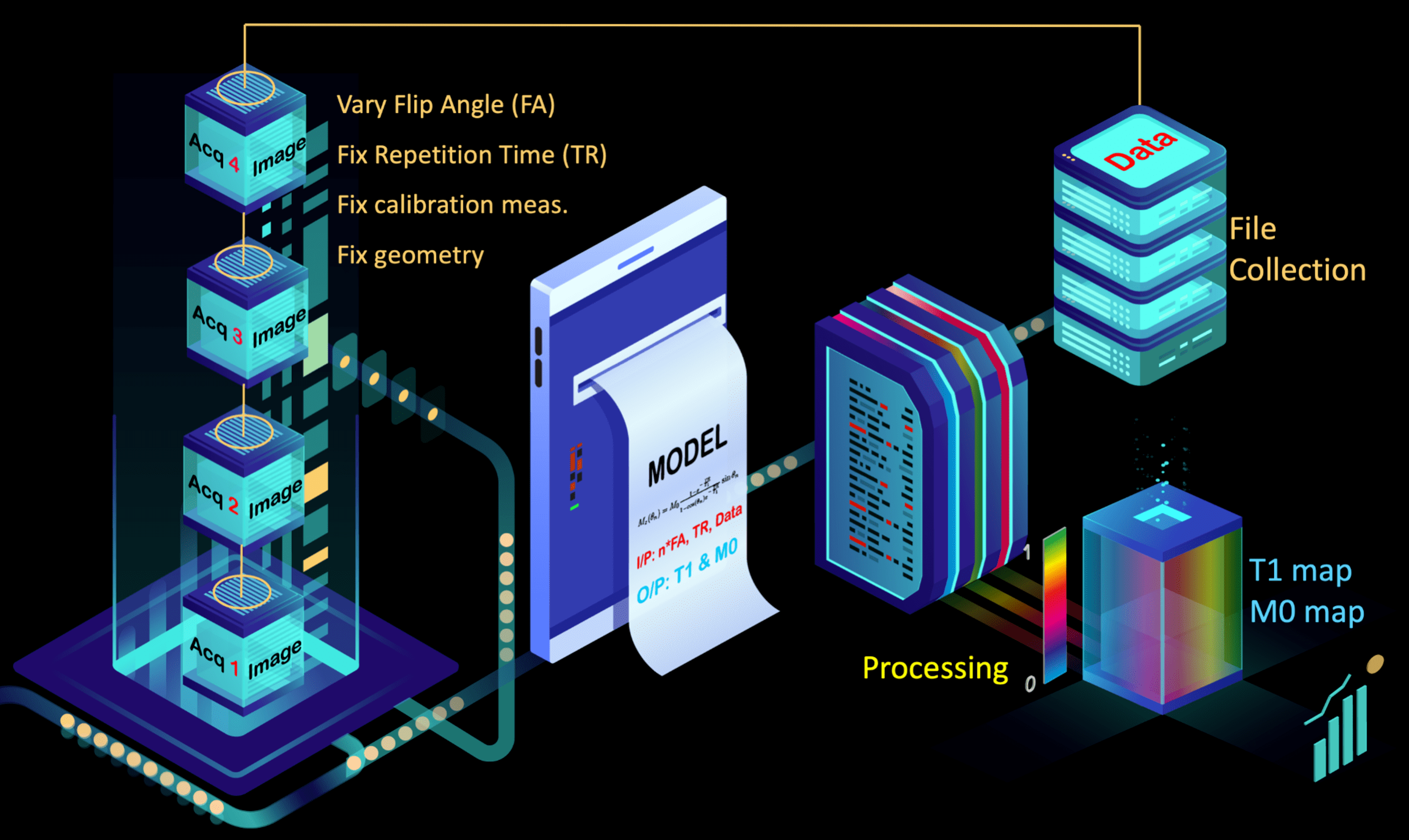

Fig. 1 – The components of a qMRI method by Dr. Agâh Karakuzu (OHBM Educational).

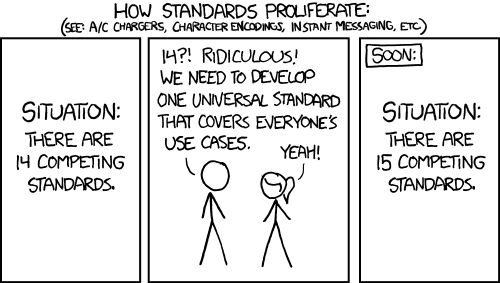

Of course, you can create your own data management system, which has the advantage of being tailored to your exact needs. However, there is a reason why you became a scientist and not an accountant, and it is quite time-consuming to write up proper documentation – i.e. documentation so crystal clear that even a government bureaucrat (or, more realistically, your collaborators and yourself in 10 years) could easily understand (and maybe even tax) it. Consequently, if you do end up making a sizable time commitment to an important but tedious process, you have a strong incentive to publish this data standard somewhere, and hopefully even squeeze a paper or two out of it… Which is part of what drives the following problem:

Fig 2. – Standards by XKCD.

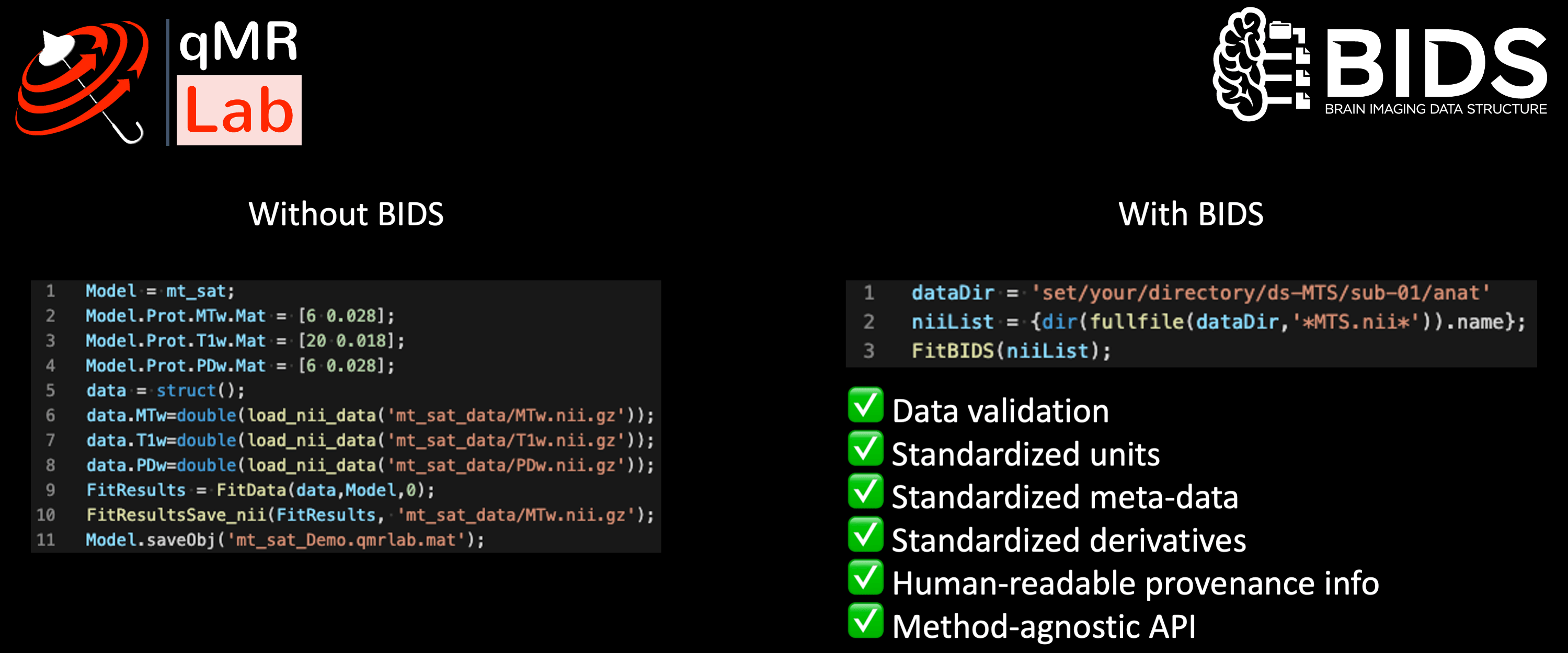

Luckily, there exists an alternative. You can save time and energy and avoid a whole series of mistakes by using the popular and thoroughly documented Brain Imaging Data Standard (BIDS) (Gorgolewski et al., 2016). **At the qMRLab, we aim to make MRI data FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (Wilkinson et al., 2016)) by adhering to the qMRI-BIDS (Karakuzu et al., 2022) data standard.** So BIDS is where we will continue the parallel between neuroimaging and genetics at an even finer resolution: let’s peek into the machinery of one individual neuron!

Just as DNA is protected inside the nucleus of a cell, BIDS stores your raw data in a separate directory that cannot be touched. And just as several RNA polymerases transcribe your DNA to RNA, which is then released into the cytoplasm, many openly available tools exist to help “BIDS-ify” your data (e.g. openfmri2bids, dcm2bids) before releasing it into your dataset directory. To avoid gaining too many genetic mutations throughout one’s lifespan, humans have a very sophisticated DNA replication error monitoring and repair system in place. Similarly, the freely-available BIDS validator ensures that your data is formatted correctly and ready to be input into the many open source BIDS apps (Gorgolewski et al., 2017), a set of open-source neuroimaging data analysis pipelines.

And if you are working with qMRI data specifically (and why wouldn’t you?), the qMRI-BIDS specification (Karakuzu et al., 2022) simplifies matters further by defining the generalizable and intuitive concept of file collections, which can include acquisition sequences such as MP2RAGE, or data collection frameworks such as Variable Flip Angle (VFA) imaging. Additionally, the qMRI-BIDS format standardizes units and enforces rigorous meta-data requirements for over 15 qMRI methods. In case you may wonder why there is no way to ignore unit standardization, here is a list of some real-world consequences of poor unit standardization. Finally, qMRI-BIDS significantly facilitates the integration of various software packages and pipelines by standardizing input and output conventions. For instance, if you want to use the qMRLab pipeline, which allows you to integrate a whole suite of qMRI tools under one umbrella ☂ (Karakuzu et al., 2020), the qMRI-BIDS format greatly facilitates package implementation:

Fig. 3 – Dr. Agâh Karakuzu (OHBM Educational)’s on the role of open-source software and community data standards.

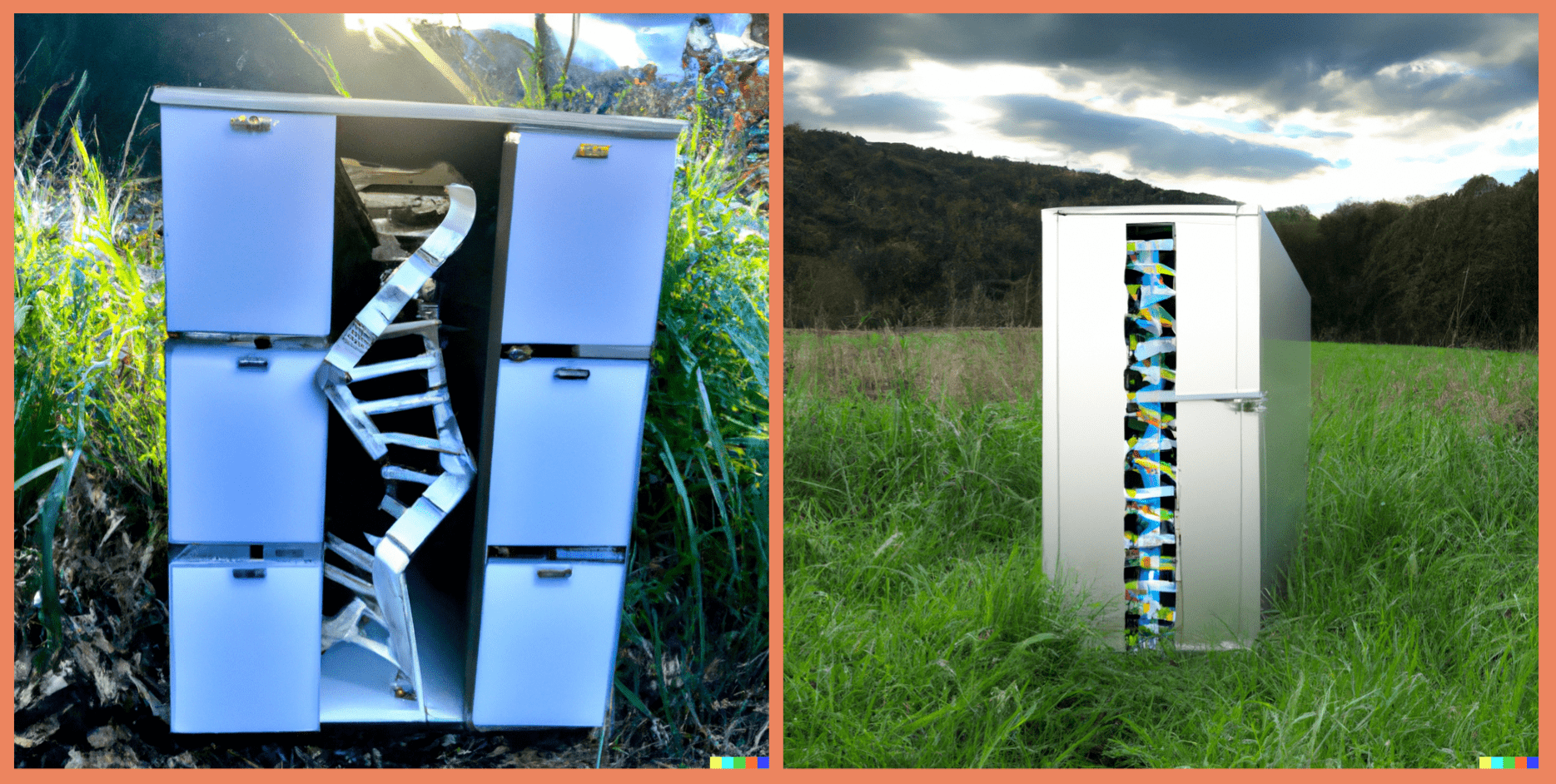

And although the BIDS specification document may seem lengthy, the learning curve is not very steep because the documentation provides sample datasets (e.g. BIDS examples and qMRI-BIDS example), tutorials and even a BIDS Starter Kit! In the long run, transitioning away from your personalized, ever-evolving and seldom internally consistent accounting system may save you a lot of time:

Fig 4. – Is it worth the time? by XKCD.

Concluding remarks by chat-GPT.

Given that chat-GPT is about to replace all scientists on Earth (kidding – I prefer the optimistic hot takes), I decided to probe its wisdom on the similarities between DNA and data standards:

ChatGPT:

“Just as DNA is the fundamental building block of life and allows living organisms to store and transmit genetic information, good data standards are the fundamental building blocks of information systems and allow organizations to store and transmit data in a consistent and organized manner.

“One of the most important similarities between good data standards and DNA is that both are essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the information they store. Just as DNA must be accurately replicated in order for an organism to function properly, data standards must be consistently applied in order for an information system to be reliable and effective. This is because without good data standards, data can become fragmented and inconsistent, leading to errors and inconsistencies that can undermine the accuracy and usefulness of the information being stored.

“Another important similarity between good data standards and DNA is that both are essential for facilitating communication and collaboration. Just as DNA allows living organisms to share genetic information with each other, good data standards allow organizations to share data with each other in a consistent and organized manner. This is critical for enabling organizations to work together effectively and efficiently, and is essential for supporting complex systems that require the integration of data from multiple sources.

“Another important difference between good data standards and DNA is that good data standards are often developed and maintained by specialized organizations, while DNA is found in all living organisms. This means that while DNA is a universal language that is shared by all living things, good data standards can vary from one organization to another, and can be developed and maintained by groups with specific expertise in a particular domain.

“Overall, good data standards and DNA are both essential for organizing and maintaining information, and share many important similarities. Both are critical for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the information they store, and both are essential for facilitating communication and collaboration. Despite some differences, the comparison between good data standards and DNA is a useful way to understand the importance of good data standards in today’s world.”

Acknowledgements.

Essay edited by Dr. Nikola Stikov. A special thank you to Dr. Mathieu Boudreau and Dr. Agâh Karakuzu for reading drafts of this essay. And a slightly suspicious thank you to OpenAI’s infant digital monsters for their chilling artistic and stylistic contributions.

References.

- Antognini, A., Nez, F., Schuhmann, K., Amaro, F. D., Biraben, F., Cardoso, J. M. R., Covita, D. S., Dax, A., Dhawan, S., Diepold, M., Fernandes, L. M. P., Giesen, A., Gouvea, A. L., Graf, T., Hänsch, T. W., Indelicato, P., Julien, L., Kao, C.-Y., Knowles, P., … Pohl, R. (2013). Proton structure from the measurement of 2S-2P transition frequencies of muonic hydrogen. Science, 339(6118), 417–420.

- Gorgolewski, K. J., Alfaro-Almagro, F., Auer, T., Bellec, P., Capotă, M., Chakravarty, M. M., Churchill, N. W., Cohen, A. L., Craddock, R. C., Devenyi, G. A., Eklund, A., Esteban, O., Flandin, G., Ghosh, S. S., Guntupalli, J. S., Jenkinson, M., Keshavan, A., Kiar, G., Liem, F., … Poldrack, R. A. (2017). BIDS apps: Improving ease of use, accessibility, and reproducibility of neuroimaging data analysis methods. PLoS Computational Biology, 13(3), e1005209.

- Gorgolewski, K. J., Auer, T., Calhoun, V. D., Craddock, R. C., Das, S., Duff, E. P., Flandin, G., Ghosh, S. S., Glatard, T., Halchenko, Y. O., Handwerker, D. A., Hanke, M., Keator, D., Li, X., Michael, Z., Maumet, C., Nichols, B. N., Nichols, T. E., Pellman, J., … Poldrack, R. A. (2016). The brain imaging data structure, a format for organizing and describing outputs of neuroimaging experiments. Scientific Data, 3, 160044.

- Karakuzu, A., Appelhoff, S., Auer, T., Boudreau, M., Feingold, F., Khan, A. R., Lazari, A., Markiewicz, C., Mulder, M., Phillips, C., Salo, T., Stikov, N., Whitaker, K., & de Hollander, G. (2022). qMRI-BIDS: An extension to the brain imaging data structure for quantitative magnetic resonance imaging data. Scientific Data, 9(1), 517.

- Karakuzu, A., Boudreau, M., Duval, T., Boshkovski, T., Leppert, I. R., Cabana, J.-F., Gagnon, I., Beliveau, P., Pike, G. B., Cohen-Adad, J., & Others. (2020). qMRLab: Quantitative MRI analysis, under one umbrella. Journal of Open Source Software, 5(53), 2343.

- Wilkinson, M. D., Dumontier, M., Aalbersberg, I. J. J., Appleton, G., Axton, M., Baak, A., Blomberg, N., Boiten, J.-W., da Silva Santos, L. B., Bourne, P. E., Bouwman, J., Brookes, A. J., Clark, T., Crosas, M., Dillo, I., Dumon, O., Edmunds, S., Evelo, C. T., Finkers, R., … Mons, B. (2016). The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Scientific Data, 3, 160018.

|

Except where otherwise noted, the content on this blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

|