On the open source landscape of MRM

Being involved in several open source projects (qMRLab, AxonDeepSeg) and initiatives dealing with open science in publishing (NeuroLibre, Canadian Open Neuroscience Platform), I was curious to know what the current landscape of open source software/analysis sharing was in my own field - MR engineering for medical applications. I decided to investigate what the landscape of open source sharing was in one of the main journals of my field, Magnetic Resonance in Medicine1 (MRM). Note that this isn’t a scientific study in itself, it was just a mini side project that evolved out of curiosity.

The broad questions that I was interested in were the following:

- What % of MRM papers claim to share code/data/scripts ?

- If they share code, what coding languages do they use ?

- Where do they typically host their code/data ?

- What’s the completeness of what they shared (e.g. ranging from being able to reproduce paper figures to never having delivered on their promise to share their code).

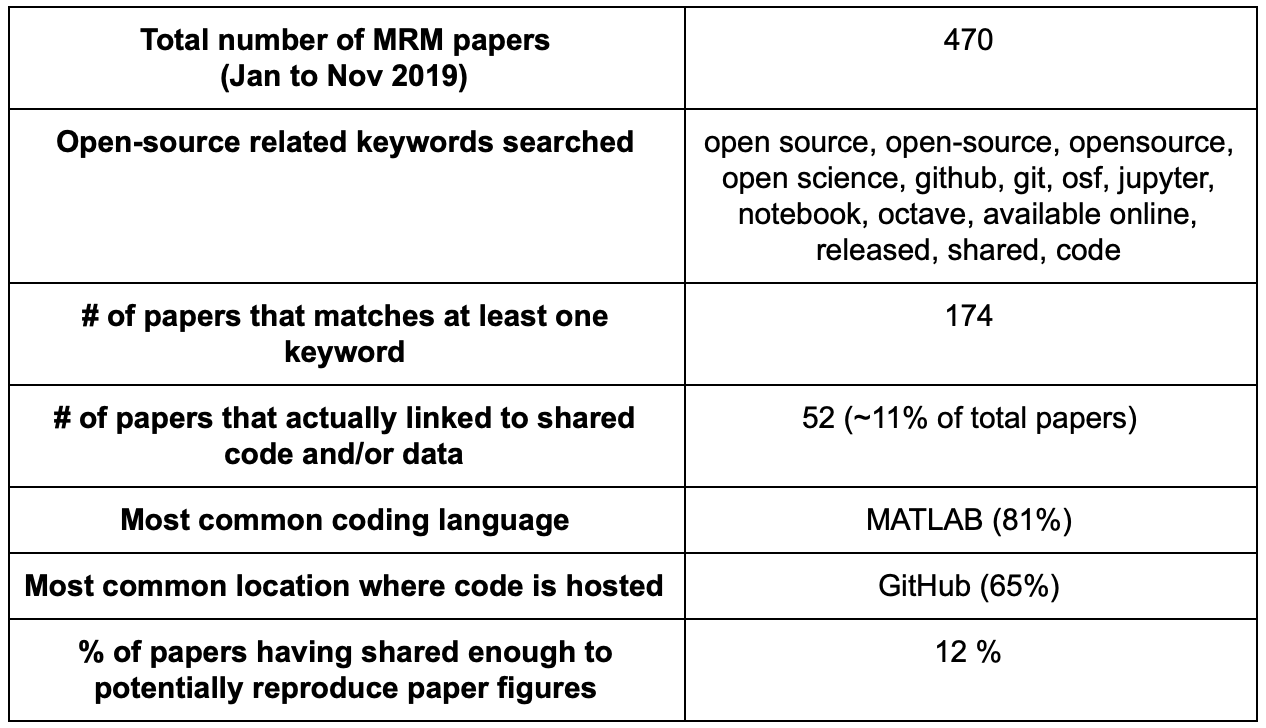

- Downloaded all papers published in Magnetic Resonance in Medicine from January to November 2019 (December issue not out yet).

- Ran a script to search for all papers that contained one of a list of keywords that may hint at containing open-source code/data.

- Compiled all the papers that matched keywords into a Google Sheet file.

- Manually looked in each paper to see if code/data was actually shared.

- Parsed through these and the external links to see if they (1) shared code/data/scripts, (2) see which languages the codes used, and (3) where they hosted their code/data/scripts.

Only 11% of MRM papers claimed that they have shared code/data/scripts developed in relation to their published work. However it may be possible some papers shared their code without reference to one of my keywords. There’s also a few instances of grey area where authors linked to code that wasn’t clear to me if it was developed for this purpose or developed previously and only used for this project.

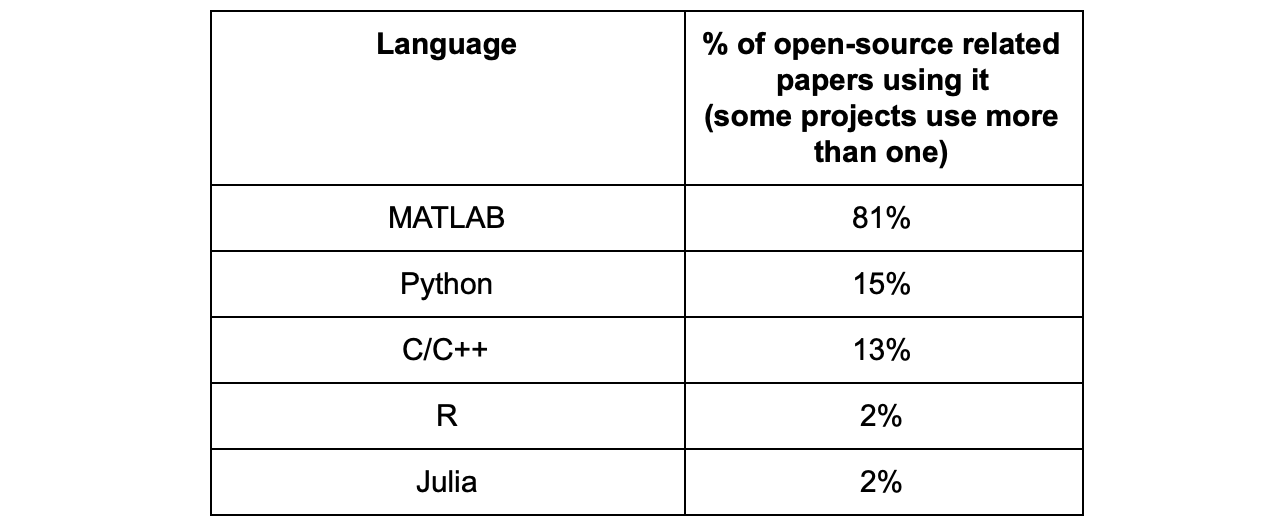

By a wide margin, 81% of those papers used (at least in part) MATLAB, whereas the second most used coding language for papers that shared code was Python at only 15%.

It wasn’t a surprise to me that MATLAB ranked first, as it’s the language I’ve encountered most at conference posters over the past decade. I was surprised however at how large the margin was at the moment; in several other fields (e.g. machine learning, neuroscience, etc.), Python is rapidly growing in popularity. Not just that, but MATLAB being a proprietary software, I expected a bit more folks that wanted to share their code to have also adopted an open source language, but that appears to not be the case at the moment in this field. There is nothing wrong with this choice per say, I myself work on an open source quantitative MRI project that uses MATLAB (qMRLab), although we try to make it mostly Octave-compatible. But I’ve experienced first-hand how challenging it is to develop a large project in MATLAB and try to maintain it over a long period of time; there is a constant need to be aware and catch up with new versions of MATLAB (which roll out twice a year) while keeping it compatible with older versions. It is also frustrating to see some widely used tools implemented in open-source languages but not in MATLAB (e.g. Jupyter notebook scripts that would run on NeuroLibre/MyBinder, continuous integration tools like Travis CI, virtual environments and containers for version & package reproducibility). These are considerations that I think many people in my field may not be aware of, and they could benefit from switching to Python for the projects that they intend on sharing.

A majority of papers hosted their code/data using GitHub, which was encouraging as this means that there are version control measures and users can track bug fixes that may occur after the paper is published. Not just that, but the readers can more easily report bugs and contribute fixes, or other new features, which benefit both parties!

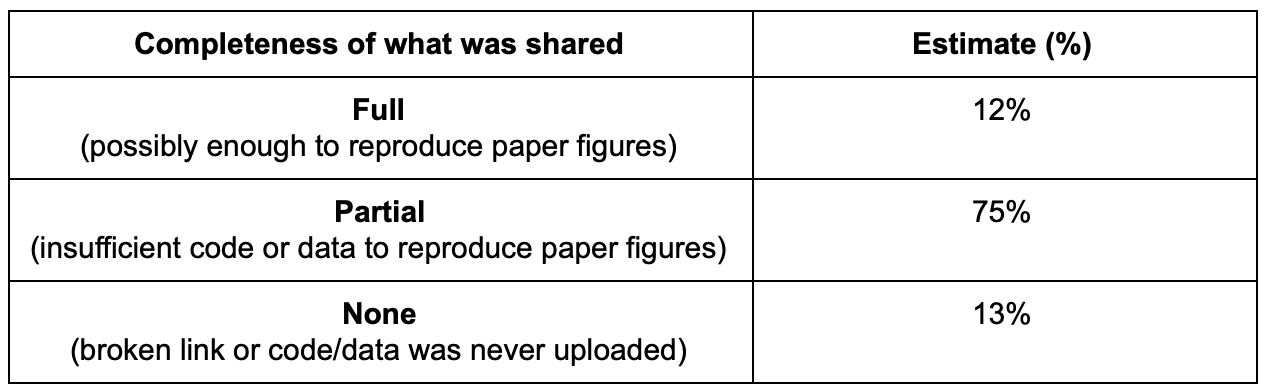

Lastly, I quickly explored all the code websites/repositories and tried to estimate (very roughly) how many of them provided sufficient code, data, and scripts that appear to be sufficient to reproduce figures from their paper.

Only 12% of papers appear to have shared enough to reproduce paper figures, and I suspect if I went in and actually tried to do so the number would turn out to be lower. The wide majority of papers (75%) ended up only sharing some example data or only their code. 13% shared links that were broken or contained no code. In some circumstances, it appears that they linked to a personal/academic website that had expired, but in most cases the authors promised in their paper to publish their code after the paper was accepted, but never did so. If you are a reviewer for a paper in the future and read a similar promise, it may be beneficial for the journals and their readers if you press the authors to publish their code/data prior to final accept or simply ask that they remove this promise if they refuse to do so, as once the paper is published there is nothing preventing them from not uploading the code (or simply forgetting to do so).

Overall, I think that what this analysis showed most is that at the moment, our field could benefit from defining a certain level of standards when sharing code/data/scripts in papers, as it appears to be handled on a paper-by-paper basis. This applies to standards regarding where the code/data is hosted (so as to avoid broken links), in reporting which languages & tools are used (e.g. code testing, continuous integration, notebooks), and in reporting how much or what is shared (only code? only example data? enough to reproduce figures?). I think defining these kinds of standards would set a higher bar for authors to aim for when sharing code, which would benefit their long term research and the field as a whole. The ideal scenario, if possible, would be to reach a point where people share not only code and data, but also scripts and containers that can completely reproduce all the figures from their papers at the click of a button.

1 Not a financial conflict of interest, but for the past four years I have been a regular contributor to a science journalism initiative associated with this journal, MRM Highlights.

|

Except where otherwise noted, the content on this blog is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

|